| O Ce Biel |

| From the Friulan song "O Ce Biel Cjiscjel a Udin" |

| Memories of 1970s Friuli |

|

|

| HomeArrivalBrandoGowanTalmassonsTerremoto |

| ReturnFoodPoemsSongsVeniceTriesteUdineseMerlot |

Terremoto |

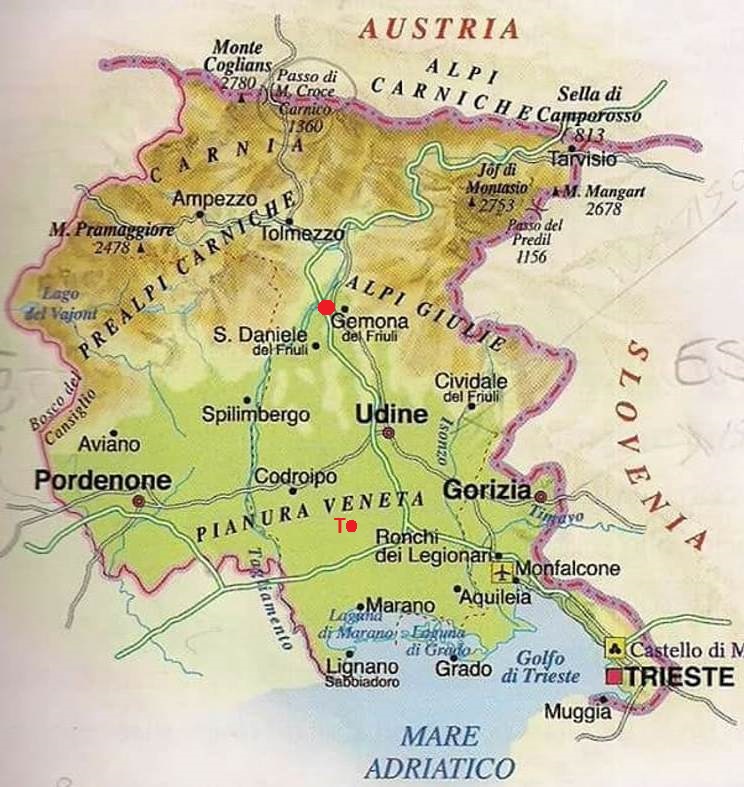

It was the evening of Thursday 6th May 1976, just before 9pm. I was teaching my English language class in the village of Talmassons (see the section of that name). The students were all from the village and surrounding hamlets, members of the Circolo Culturale who had organised the year-long event in the interests of broadening their horizons. It was an intensely hot evening for early May, dry and faintly oppressive, possibly more so because of Talmassons' position on the flat plain south of Udine running down to the sea at Lignano. Fortunately we were in one of the cool classrooms of the primary school, a solidly-built single-storey building on the edge of the village. We had started at 8pm and were just about to take a short break. Seconds after 9pm, I was standing with my back to the outside wall of the classroom, ready to take a breath of fresh air outside the school with the students. There was a loud rumbling behind me, outside, like a large truck reversing. A pause, then a much louder grinding roar, the walls screaming. The classroom shook from side to side, the floor moved; it was difficult to stand up. We all (well, not all, it turned out) ran for the classroom door, then turned left down the corridor to the main entrance, a distance of 30 metres. It was a broad corridor, but I remember being thrown from one wall to other. Outside, I swear the gravelled playground was rolling like a sea swell. Less than a minute and it was over, still again and very hot. We were all in a group, except for one member of the class. Federico Zanin, the railwayman, had not joined the panic-stricken exodus but stayed behind in the classroom, tidying books. He emerged quietly from the school, smiling ruefully. We talked animatedly in the courtyard, trying to establish what had happened. It had pretty clearly been an earthquake. What we didn't know was the extent. That became clear over the following days. Below is a map of Friuli. Talmassons is marked approximately by a red "T" and dot. Gemona del Friuli, the most affected town to the north, is indicated with another red dot.  The first quake on 6th May was measured 6.5 on the Richter scale. This was followed by at least two more significant tremor ("scossa") groups on 11th September (5.8 at 18:31, 5.6 at 18:40) and 15th September (5.9 at 05:00, 6.0 at 11:30). The epicentres are circled 1, 2 and 3 in the darkest red shaded area. 989 people died. Gemona had the largest number of fatalities at 325. 2,607 were injured. People were re-housed in "prefabbricati", temporary homes. The percentages of the population for certain towns or villages in such dwellings are listed at the bottom. The numbers are from March 1978, nearly two years after the event. The biggest proportion was in Lusevera, at 95.3%, albeit on total inhabitants of about 600. Immediately after the 6th May quake, the US military from the airbase at Aviano near Pordenone built tent villages on the flat farmland to the west of the hill towns. We visited one near Gemona at Trasaghis - more of this later. The coastal resorts to the south took in many of the displaced ("sfollati"). Lignano took 19,076, Grado 6,299, Bibione 4,566. A total of 32,276 left the region at least temporarily. The most severely damaged areas, designated "disastrati", were logically near the epicentres north of Udine. Talmassons, 20 kilometres south-west of Udine, 58 kilometres south of Gemona, was barely affected. In the moments after the quake, I therefore had no understanding of the mayhem further north. I drove back to Udine. At around 11pm, the city was busy as I entered. Nobody had any inclination to be indoors, certainly not to sleep. Portions of the inner ring road with grass dividing strips already had tents erected. I went to bar Da Brando, where as expected I met several other teachers from the Oxford School. I have no idea when we went to bed that night. The Oxford School, in Via Paolo Sarpi in the historic centre of Udine, had sustained some damage and was closed for a period. We therefore had time on our hands. Sue had a bizarre windfall. She found a 1,000 deutsche mark note in an Udine gutter. Generously, she decided to put this money to the cause. She hired a van and we were able to go up to the earthquake zone to do what we could to help. We didn't have many useful skills. We just drove up to see what we could do. I remember going to the tent city in Trasaghis days after the 6th May quake. Row upon row of tents, one to each family, in torrential rain. One family needed help retrieving possessions from their house in Gemona. We went up there, watched as they scrabbled in the ruins and brought back any useful and intact items. When we returned, the black-clad "nonna" was cooking in the tent on a camping stove and insisted that we should eat with them. In the midst of extreme loss, they still wanted to give through the sharing of food. Majano, where 119 perished, and which we visited one hot day following 6th May, was a scene of dust and destruction. Near the centre was a recently-built small block of flats, once six stories high. It had collapsed straight down on itself, a minor version of the 9/11 twin towers. The build quality of the flats was questioned. A grim dark joke was doing the rounds, an argument about responsibility between Bricks, Timber and Mortar. After much to-ing and fro-ing, Mortar declared: "It couldn't have been me - I wasn't there." Survivors were still presumed trapped. We heard that some standing on the upper balconies had simply descended to ground level and walked away. Helpers of all description (the Visualoop data map has a breakdown of national and international assisting groups, "reparti italiani" and "reparti stranieri") swarmed over the debris, removing rubble by hand. It was the only time I witnessed the dead. A soldier uncovered a body under the masonry, an arm reaching up to the sky. Our friend Ermanno in Talmassons had a brother, Angelo, who was a priest in Artegna just south of Gemona. A tall dark man with the most delightful open face, animated in expression and gesture. He and other members of the local clergy were central to the recovery process, not only in giving emotional help to parishioners, but also in keeping a strict eye on the deployment of support funds. Returning to England in the late summer of 1976, I gave some talks to raise money at schools in my home-town Worcester. The proceeds were handed over to Angelo; I was sure that they would be used effectively. We went up to Artegna with the Talmassons villagers most Sundays through that spring and early summer. Starting the day in a makeshift bar off the main square, it was the earliest I'd ever drunk alcohol. We were all given an expresso coffee accompanied by a shot of grappa. A "heart-starter" as the actor Oliver Reed called it. What did it all look and feel like? If you went back to places you had known before the earthquake, you could usually orient yourself by the street layout that remained. But the old stone-built houses had gone or were severely disfigured. The fronts of the houses might have disappeared, exposing bedrooms complete with furniture. On hot days the air was thick with dust, which had a strange stuffy odour, not quite decay, but close. After rain, the streets were awash with mud. Below is a picture of Buja, near Artegna.

We met a couple called Gustin and Maria in Artegna, who lived on the main street running south from the main square. You entered the property through an arch, the house on the right, their land beyond, where Gustin's metal-working "capannone" was situated. The house was damaged, so they lived in a large hut set behind. Maria was a kind, radiant woman who always welcomed us with grace and generosity; in later years I took my parents, family and children to meet them. Gustin was a red-nosed Friulano countryman who loved his wine. After that night of 6th May, he never drank again. He said that he'd not realised before how little he'd done around the house to help Maria, but from then on assisted with shopping, cooking, cleaning. They had a little dog born on the night of the earthquake, so she was called Scossa ("tremor"), or Scossute in the Friulan diminutive.

North-east of Artegna, further up into the mountains, the beginning of the Alpi Giulie, is a village called Montenars. We went there a couple of times. Again, we had no particular skills to offer, just our hands. We cleared the rubble from the local bakery. A significant character in the village was Don Francesco Placereani, or Pre Checo, a left-wing non-conformist priest.

Born in Montenars in 1920, he died in Udine in 1986. He was an orator, writer, translator and Friulan activist. I stood next to him by the remains of his house. A wild, unkempt man was scouring the ruins, trying to rescue the library, which contained the priest's own writings, many of them original scripts. Pre Checo said to me, "I wish he'd stop. I'll just write some more." The picture below is of his temporary hut. From left to right, Giulio Zanin, Pre Checo, Charles, Federico Zanin and me, with bottiglione of red wine provided by Pre Checo.  Notice the vines behind. The earthquake didn't kill them, nor the rest of the crops. The damage was all to man-made construction. The Friulan generosity in the face of adversity is a recurrent theme. We helped a farmer just outside Artegna, simple manual assistance. I took my parents to see him and his family some months later. On a trestle table in front of their damaged house, they laid out home-made salami, sheep's cheese and red wine. Why were they thanking us in this way? Lucia Beltrame, daughter of Carletto from Talmassons, sent me an email on the 40th anniversary of 6th May thanking us for our contribution (see the end of the "Talmassons" section). What contribution, such meagre help? I believe it was thanks just for our presence, being witnesses to their strife, taking an interest. Not much, but important to them. What of recovery? The management of restoration in the region is viewed as a success, unlike many such ventures that fell prey to corruption and waste. Below is an aerial photo of Artegna in recent times.  |