| O Ce Biel |

| From the Friulan song "O Ce Biel Cjiscjel a Udin" |

| Memories of 1970s Friuli |

|

|

| HomeArrivalBrandoGowanTalmassonsTerremoto |

| ReturnFoodPoemsSongsVeniceTriesteUdineseMerlot |

Gowan |

I can't remember meeting Gowan for the first time, which is unusual with someone who becomes such a great friend. I spoke to him on the telephone, four days before I arrived in Italy, in what was effectively my job interview - a rather less rigorous selection process then. After that, I have no real sense of him until New Year's Eve 1975. My first few weeks in Italy had been uncomfortable. Not desperately wrong, just that things hadn't really clicked. I'd arrived after the others at the Oxford School, in late November 1975, and had some catching up to do. Most of the extra elementary classes at outlying customer sites had fallen to me, so I travelled quite a lot and was rarely at the school. There was a lot of preparation to do, or it seemed that I needed to do more than others. My Italian was coming on slowly. In short, I didn't feel fully connected to where I was and what I was doing. So it was with some relief that I went away for Christmas to join my parents in Malta. They had rented a typical but plain villa for a week, and we spent a happy reunion pottering around the main island and Gozo, its smaller cousin, sightseeing and bathing. It was a welcome break - a chance to rest and be looked after. Arrangements had been made that I would join Gowan and others for New Year's Eve, which meant that I had something - I wasn't sure quite what - to go back for. I met up with Gowan in Udine on my return - not just him, but the party I was going to spend several days with. Gowan was an elegant man. He was pale-skinned, but darkly bearded, and at that time wore a black fedora hat and sunglasses. With his customary business suit - Gowan always wore a suit, sometimes a light beige summer version for variety - the impression he gave was lightly gangster-ish offset by a genuine and quaint Englishness. He'd been in Italy for some time, joining the school perhaps 10 years earlier, now the commercial director. Based in Venice, his first love was always Udine, where he had set up the local Oxford school over the previous 5 years. He was a hybrid, very Italian in some respects, very out-of-date English in others. He would speak wistfully of real ale, a good English pint, but his heart lay with a classic Merlot from Friuli.  The rest of the party was made up of Fran, Gowan's wife, and their two children, Alexander and Elizabeth; Andrew, another teacher and Gowan's closest friend, and his girlfriend, Fausta; and Francesca, a friend of Fausta's. I wasn't close to these people, so it felt somewhat alien - but that was going to pass soon, if only I had known. There was also the car. Gowan had a beautiful grey Jaguar saloon, a Mk2 with all the traditional leather and wood. There was sometimes a large plaster zebra that Gowan had won at a fairground resting on the rear window shelf.

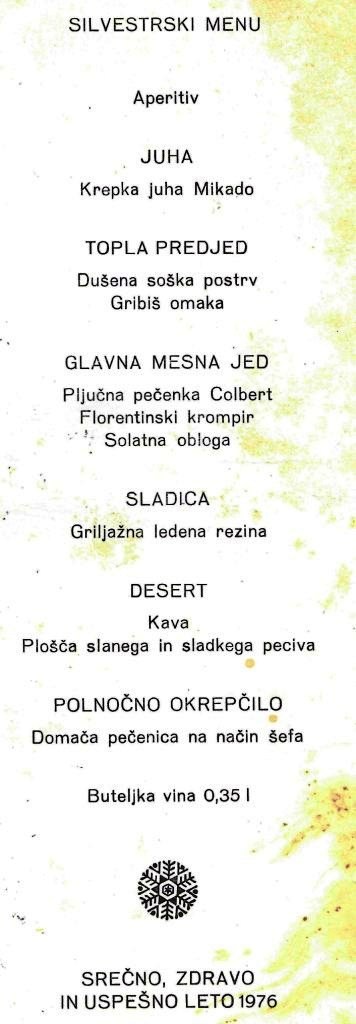

After much last-minute hunting for a place to stay for the big night, we found and booked rooms in Bovec, just into Yugoslavia. We took off in the Jag - there must have been another car, but it's not as memorable - to Cividale, then up the valley of the Natisone river and over the border. "God's own country", Gowan would always say - and to this day, I feel the same about that area. At that time, and as a raw 23-year-old, it all felt very exotic; going abroad was not a novelty, but the hint of the east was. We crossed the border and reached the Hotel Kanin, nestling beneath the mountain of the same name, in the early evening of December 31st 1975. It was recently built, very modern and elegant, a low-rise construction with six or seven floors presenting a sloping white façade of balconies. Surprisingly smart, because this was still a communist country. When you came through the almost incidental checkpoint - two sad youths lolling back in their chairs smoking cigarettes - between the two countries, all roadside advertising stopped, a real contrast with the loud promotional clutter lining most major Italian roads. It was Tito's Yugoslavia, a liberalised mixed economy where such developments were appearing with regularity. Here's that evening's hotel special menu. Have fun translating :-)

At dinner, we saw a very elegant, striking woman, blonde, dressed in a tight-fitting cream silk dress, low-cut with thin shoulder straps - an ethereal effect overall. Throughout the evening, she kept appearing, alone, in the bar, on the staircase up to the rooms, in reception. We christened her "Thin Silk". The staircase wound its way up round a central well. At each level, set back from a rail over which you could see all the way down to the ground floor, was a kind of mini-lounge with sofas and armchairs. Late into the evening, we occupied this space on the top floor. We played the Adverb Game. In this, one of the group is sent out of earshot and an adverb is chosen. The excluded player returns and has to guess the word by asking the other members to act something out in the manner of the adverb. I later played the most memorable version of this at Gowan and Fran's flat in Venice, where Gowan's extremely proper mother was asked to recline "erotically". If this was not toe-curling enough, a visiting English acquaintance, Tim, seeing Esme's gallant supine attempts to transmit the meaning, declared in his strong Lancashire brogue that the word was "fook-ing-ly". Still, these moments seemed to pass in those days without much damage done nor offence taken. That evening in Bovec was the first time I had played the game, and, like most things I did with Gowan, it still brings a smile. At one point, I decided I needed a break and said I was going for a stroll downstairs and out into the fresh air. Gowan and Andrew insisted that I let them know if I saw the blonde woman. I got down to reception and sure enough she was there, emerging from the bar, alone, holding an unlit cigarette. Just me and this apparition, and the hotel staff behind the counter. I was under orders, of course, so raised my head up towards the top floor of the stairwell, and bellowed at the top of my voice, "THIN SILK!" There was suddenly, in contrast, a deafening silence. Nobody around me, of course, had any idea what I was saying or why. Then, imperceptibly at first, came the sound of approaching thunder, which grew quickly into a roar, like horses' hooves, spiralling down. Gowan and Andrew swung wildly off the bottom stair and just managed to pull up short of our new friend. "Signora," Gowan said, reaching into his pocket, "may I offer you a light?" Over the next two years, we would frequently meet in "God's own country", that wedge of foothills beyond Cividale, and in the rolling wine land stretching down towards Trieste, the "Colli Orientali del Friuli" - again, the eastern promise in the name. Gowan owned a ramshackle cottage up a deserted lane there for a while; that too faded away. Cividale itself was - is - an exquisite little town, perched on the banks of the Natisone river, which cuts through stone far below the high vaulted bridge that separates the two parts of the town, the "Ponte del Diavolo". A little further along the river through very narrow streets is the "tempietto", a little 8th century Longobard chapel. The main square, Piazza Paolo Diacono, like most of the centre of the town inaccessible to motor traffic, is a delightful L-shape, with covered-arch walkways, shops and cafes. It is in this square that the annual wine festival is held. We would go every year, and stay in the Tamburino, a traditional inn only 50 yards from the main event. It was run by Signor Mario and his wife. He was a lording-it, fill-the-surrounding-space, dramatic plump man; she was smaller, a straggle-haired, bespectacled shadow, who nonetheless wielded much power and dissipated the chaos that Mario would invent. Gowan and Fran were frequent, valued and loved customers, and the house rules were relaxed and welcoming. Alexander and Elizabeth slept in wooden drawers in their parents' bedroom, made up by the Signora herself. She would watch over the children when we all went out.  The square would be transformed during the festival by the arrival of rustic kiosks selling local wines, salami, cheese and other farm produce. The evenings were perfectly warm. It was very busy; going to these "sagre" is popular in the spring and summer months. I would usually run into friends from other parts of the region. There were headaches after the Cividale wine festival. I remember waking one morning in one of Signor Mario's lovely - but actually not very comfortable - rooms. It was a twin-bedded room with two wood-and-lumpy-mattress single beds, Sue and I in one, Andrew and Fausta in the other. Sheer hell. As light forced its way through the blinds, I wanted water and thought I'd do the decent thing. I went downstairs to the main bar in some dishevelment and met people doing normal things and feeling perfectly well. La Signora was there and tried to help. "Due bottiglie di acqua minerale, Signora", I said, "frizzante, per piacere". "D'accordo, Signore." I took the two bottles and four glasses up to the room. Inside, I opened one of the bottles, managed the fizz, poured a glass, went up to Andrew and prodded him. "Water", I said. Andrew opened one eye, and replied: "Take it away, please, Charlie. It's TOO LOUD." One of the Udine school end-of-summer-term parties took place at the Tamburino. There were about thirty of us, including Toni, the car park attendant from Piazza Duomo in Udine, a great friend of Gowan's. His wife Irma, who cleaned the school, was there also. The guests were a mixture of English and Italian, all at two long tables in the dining room through the double half-glazed wooden doors off the main bar. Mario was particularly good at roast meats, which he would serve sliced on large white oval platters. It was after eating these that the annual conga round the square was proposed, so off we went. In the middle of the square is a fountain, a waist-high basin of water with a statue at the centre. I must have lost my presence of mind. I decided to auction my clothes from the top of the fountain, so climbed to the top, took off my socks and asked the gathered friends to start bidding. I didn't do very well, and was disappointed to earn only 1,400 lire for all my clothes, a derisory 75 pence. There was one other magnificent conga. Another school celebration meal, this time in the tiny hilltop village of Tribil di Sopra, beyond Cividale again, overlooking the border. We took over the main room of the Ristorante ... well, the only restaurant. A traditional meal, then dancing! The tables were cleared away and we filled the floor. At one stage, Gowan and Fran danced with the coat stand, still laden. Then the conga. Gowan led the line round the restaurant, out of the double front entrance and into the main square. He spotted one house with its lights on, led us up to the front door and knocked. A farmer opened the door and Gowan greeted him. He then showed his British passport, and led us all right through the hall of the house and out of the back door. There confusion reigned, as it was pitch-black, and many of us fell over in the farmer's back yard. If we sound like dreadful public school louts, I think we probably were (although few had been to a public school), yet it felt different to the so-called "high spirits" of such university excess in England. I don't think we really ever offended anyone and it felt like simple playfulness. Or so I would like to believe. Gowan and his family had moved to Venice from Udine when he became overall commercial director of the group of schools, because the headquarters was there. They lived in a top-floor apartment in a side street not far from Piazza San Marco called Calle dei Preti. It was in a typical old "palazzo", but modern, comfortable, elegant. When you rang the doorbell at street level, you'd then look up to the top floor and wait for somebody to poke their head out between the green shutters. I visited often, always with a great sense of anticipation. I loved the train ride from Udine (or Conegliano Veneto when I had moved there) and the arrival at Santa Lucia station, that mystical moment when you walk through the exit onto the broad steps outside, the Grand Canal and Venice before you, the ordinary world behind. Then the boat trip, sometimes on the fast "diretto" to San Marco, or the more leisurely larger boat all the way down the Grand Canal if I had time. The first time I arrived in Venice was on a bleak winter's evening. The fog swirled all around the boat, and through the alleyways that led to Gowan's flat. It's at this point I realise with some sadness that this is a man I knew in different periods of his life. He was a lion when I first met him, in his prime. In the previous years he had been very successful in building the school business in Udine, and had an aura that preceded him. He was a touchstone for those around him, often a centre of plans and occasions. Meeting Gowan for an evening promised something different, usually very funny. He loved Italy, Friuli in particular, and that passion transmitted itself to others. He in turn cared about the people he knew, and valued their qualities enormously. There was so much laughter, so much it hurt; I can remember Gowan and I holding our stomachs in pain on frequent occasions. Yet there was a very serious, almost moral side, to do with approaching any job with professionalism, and doing the "right thing". He was wild and, as we well know now, deeply self-destructive. But there was a core of decency and honesty underlying all his actions. Fran was his wife in those early days in the mid-seventies. As I was leaving Italy in 1979, the process of their separation had begun, and later Gowan started living with Fausta, who had been married to his great friend Andrew in the Udine glory days. In the mid-nineties, Fausta left, and Gowan lived alone with their son Patrick in an apartment in Mestre. It really did all go wrong. The times with Fran and Gowan were so memorable for the rest of us. A great welcome at the flat in Venice, mad roaming through the hills beyond Cividale, eating, drinking, getting some hard work done, laughing, mixing in with their children. They seemed - often said of friends in ignorance of what is really going on - such a good team. As time passed, I understood more about Gowan and how he was restlessly attracted to the dangerous. Hence the pull of Fausta, someone with an animal quality, sensual. I know Gowan was happy in this period. He accepted all the responsibility and consequences of his errant tendencies without song-and-dance. But Fausta moved into the flat in Calle dei Preti and it just wasn't the same. Instead of an eagerly-awaited evening of hilarity, warmth and companionship, going there was only a visit. There always seemed to be some threat hanging over the Calle dei Preti tenancy in the later years of Gowan's stay, and finally he, Fausta and Patrick moved to a large apartment in Mestre at the top of an ugly modern tower block near the centre. Not the same magic. I visited with my family in the mid-nineties, after we'd been up to Udine to stay with Chris. Gowan wasn't well then. Hair grey and thinned, still slim, but painfully so. Moving with a little difficulty, the result of some hit-and-run accident on a zebra crossing. Blotchy, even raw scabs on his forehead, and the shakes he'd always had were more pronounced. His business - he'd left the Oxford School 15 years before and opened a language student placement agency - was surviving, but for how long? His working hours seemed erratic. He rose late - Patrick got himself up and off to school - and spent a couple of hours on the 'phone. At midday he'd go down to the piazza and meet a few old muckers at the bar. An afternoon nap, and then re-start down in the piazza at six. The flat was clean, but sparse and musty. I had wondered about calling in when I returned for my 50th birthday jaunt to Udine in 2002. I felt I ought. The truth is that I feared further deterioration and couldn't face it. There was another embarrassment. He had called me some months before asking to borrow money. His business had failed. Something about a broken fax machine. I didn't have the money to give him; I wouldn't have lent it. In early January 2003, I called Gowan to wish him a happy new year. Patrick answered the telephone and told me, "Papa died on 29th December." I called a few people in Italy. They hadn't heard. I eventually got hold of Andrew, who gave me some information about the funeral that had already taken place, arranged by Gowan's eldest son, Alexander. Nothing else. I tried ringing Patrick again, but got the answer 'phone, eerily still with Gowan's voice delivering the recorded message. Vanished with only the smallest of traces. The lonely disappearance of the lion I'd known. Gowan once stayed the night at Sue's and my house outside Conegliano Veneto. It was the summer wing, perishingly hard to keep warm in winter, of a Venetian villa just into the foothills of the Dolomites in a village called Colle Umberto. A beautiful place, owned by a delightful, elderly couple from the minor Italian nobility, huge Anglophiles. When you went out of the back door of our quarters, you looked straight ahead across the lawn, then on down over the Veneto plain. To the left was the adjacent wall of the main house, and in the far right corner of the lawn was a stone well. It was late, maybe two in the morning. We were outside in the warm summer night, chatting with Sue's sister Jude, who was visiting from England. Gowan had an idea. "Charlie, I want to play wolves." "Erm ... sorry?" "I want to crawl round the garden pretending to be wolves." So we did. We crawled on all fours out to the well, growling. In line astern, I remember, me in front, Gowan behind, slapping my heels to make sure where I was. Of course, it wasn't enough. We decided we should invade the main house, the home of our landlords, the Count and Countess Verecondi Scortecci. There was a side door that was usually open, and in we went. Growling more quietly now. It was pitch black, but we made it through the dining room, the gloriously elegant sitting room and back out. "Rolling down the long side of the Rialto Bridge at midnight wearing a business suit." A game invented by Gowan, which I played only once. The Rialto Bridge in Venice forms an arch over the Grand Canal, with small shops on either side of the central steps. Yes, one side is longer than the other, the one closer to San Marco. At about half-past eleven, we took off from Gowan's flat, formally dressed as required, to give ourselves time to reach Rialto by midnight. As the hour approached, we lay down on the highest point. Church bells rang, and off we went, spinning like children down a sloping field in an English summer. Not many people have done this, and too few remember Gowan. |