| O Ce Biel |

| From the Friulan song "O Ce Biel Cjiscjel a Udin" |

| Memories of 1970s Friuli |

|

|

| HomeArrivalBrandoGowanTalmassonsTerremoto |

| ReturnFoodPoemsSongsVeniceTriesteUdineseMerlot |

Da Brando |

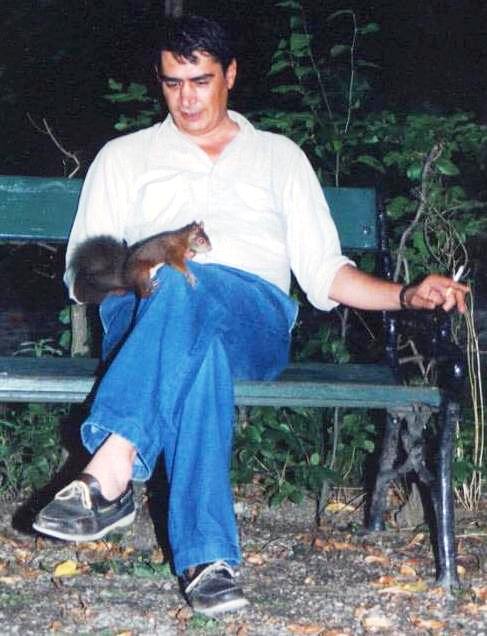

Da Brando - or Neveo's as we used to call it - wasn't really a very smart bar. It was on the east side of Piazzale Cella, a traffic-ridden roundabout of a square on the Udine inner ring road, at the exit point to the south-west and the motorway, close to the Venice-Vienna mainline railway. Da Brando was one of the older buildings facing the square along with Pozzo's just up the pavement. Next door was the Astoria cinema, which showed soft-porn films and was busy on Sunday afternoons with soldiers from the south doing their military service in Friuli. Opposite was a large modern tower block which housed Da Piero's pizzeria at its base and Radio Friuli on the top floor. It was a noisy place, often dusty in summer, with an Agip petrol station right in the middle of what should have been a pleasant park. The bar had by the time I arrived in Udine already become a focal point for my colleagues. Before us it had been a favourite haunt of Don and Sarah, an American couple who had taught at the school. They had a remembered, almost mythical status both at the school and Da Brando. In this present era the Oxford school teachers had fallen in with a great crowd who met there regularly. I joined the group and was to spend long nights with my head filling to breaking point as I learnt Italian. Neveo's front bar opened on to the pavement. If you were arriving by car, you either threw it away on the pavement right in front, or drove through an archway to the left of the entrance and parked somewhere in the scruffy yard at the side of the building. If you went into Neveo's via the front door off the street, you'd come into a simple room with the bar on the right, and four or five square tables in the rest of the room. The counter was, it seemed to me, very high - at armpit level, so you could comfortably raise your elbow and slide it onto the surface. This proved useful through the evenings when you needed all the help you could get to remain upright. Behind the bar was the usual array of drinks that you never see anywhere else - Scotch brands unknown in Scotland, sweet amaretti, digestivi. Entering Da Brando was always special to me. If alone, I'd look out for Neveo or his wife, maybe some of the other regulars. Always a sense of expectation. If in company, it was just a matter of finding the most comfortable place, to drink, to talk. Sometimes we'd sit there for hours, doing little, talking a lot. You then moved through into the other rooms. The first was where cards were played. The classic game was Briscola, a game so competitive that it was barely legal. There were three or four tables in a room full of trophies and football photographs. Neveo was a keen supporter of Udinese, president of the fan club, and host to pre- and post-match festivities. Then a door into another room. This, and the next room, which was much larger, were for dining. The open-plan kitchen straddled the two. The evening I first visited Da Brando, Neveo was serving up small birds "alla griglia", heads and little beaks still attached. Years later, when I took my 18-month-old daughter to visit, she was given a personal tour of the kitchen. The far room had several long tables, often populated at lunchtime with groups of well-dressed businessmen. They could have been members of a Masonic lodge. Given Neveo's presumed affiliations, they probably were. Why was this bar so special, such a home? It wasn't in the middle of town where the chic drank. It wasn't especially comfortable. It was a bizarre, friendly, slightly dangerous place, full of characters that you would never meet through business or normal social engagement. Like Gianni, the squat Neopolitan with a flat boxer's nose who sold his leather goods in the car park at the Yugoslav border beyond Trieste. Or "Stanlio Unwinio", nicknamed after the old British comedian because he spoke in a torrent of incomprehensible gibberish. He would sometimes stand in the middle of the front bar imitating a telephone exchange by pulling on his braces. There was "Speedway" (he loved the sport, knew all the star British riders, travelled to events all over the world), a blonde, spiky-haired, thickset bruiser with a rasping voice, who ran the local wet fish business. I was always happy to end up there after an evening out, which is what we often did. Sometimes being there was spectacular, sometimes it was ordinary and even dull, but it didn't really matter how it turned out. You always hoped it would be "one of those nights", but accepting the duds was part of the game. And Neveo. Handsome, dark, usually well-turned out in casual gear. A hint of menace in his features. He had a strange flapping gait, as if he were wearing slippers. He was an Udine man, but could have been from the south. I wouldn't have picked him as a friend, but feel he still is. He'd never be reliable and attentive, someone who would seek you out to see how you were. He'd give you time on his own terms. I usually had a great welcome on arrival, but if Neveo had something more pressing to do, he'd do it. However, he could give you moments to remember.

There was an old man nicknamed Nelly who would fall asleep at one of the tables in the front bar. One evening, Neveo walked over to Nelly, who was sitting there with one foot crossed over the other, drenched Nelly's right, suspended foot with lighter fuel and set it alight. Nelly woke up, stamped out the fire and went back to sleep. My friends Guy and Ian visited from England and we sat in Da Brando. It was quiet and Neveo had little to do. He was perplexed by the state of Italian football and gave us the most animated view of its condition, in which he ranged around the front bar with arms and legs flying, berating those in control of the game. Sue and I lived in a dreadful flat round the corner from Neveo's. Really, I mean dreadful. You left the bar and turned left, past the Astoria and then under the bridge which carried the mainline railway from Venice. Even the Romulus, the Rome to Vienna express, passed this way. Immediately through the 30-yard tunnel under the line the road turned sharp right and 24 Via Pozzuolo was 100 yards along on the left, the ground floor flat in the last of the two-storey terraced houses opposite the high railway embankment wall, set back behind a raised pavement. These houses were traditional in design and could have been quite attractive but for their location. The bedroom looked out from the front of the house at the high wall, so the view wasn't great. At night, there was the squealing of brakes and metal wheels on track as goods trains were marshalled above. The road between the house and the railway also happened to be the main route out of town to the motorway and the coast, so trucks would grind past the house at any time of day. As they came out of Piazzale Cella, under the bridge and into the Via Pozzuolo turn the drivers would have to drop into the lowest gear. They usually hit high revs in 3rd gear outside our bedroom window. We never opened the shutter in two years of living there. That wasn't all. Behind the house was a branch line of the railway and beyond that the Safau factory, the largest foundry in Udine. Huge thumping noises came from this and sometimes a drifting reddish orange cloud of dust. The rent, however, was incredibly low, so what we saved could be spent on eating out and skiing. We would often pile back there with friends after late nights out because you simply couldn't make any more noise than was already being made. It had a small yard behind, mostly covered by a grapevine. Neveo decided one year that we would make wine and provided all the equipment. We filled a large green tub with the grapes and trod them with our bare feet and pressed the last drops out with a traditional "torquio". When the time and moon were right, we made 70 bottles. Unfortunately, it was horrid, the product of our poor skills and a weak grape called "fragola". We'd drink it at night when our palates were already ruined and inflict it on unsuspecting guests. Charles' friend Guido, who made his own wine down towards Lignano, came round and had a glass. After the first sip he sought words to commend it: "Non č ..." Pause. "... Non č ..." Long pause. "... Come lo diciamo? ..." Longer pause and then capitulation. "... Non č ... buono." Neveo maintained the pretence that it was good and also that we had lodged a never-ending supply with him. We'd turn up at Da Brando when he was in a good mood and he'd demand that we celebrate with a bottle of our "Fragolino" - "I think I've got just the one bottle left!" Of course, it wasn't our wine, but frequently tasted just as bad because Neveo could push up a roughish bottle of red. Members of "the Brando Crowd" were unfortunate to drink quite a lot of the genuine Fragolino and they were always very kind about it. This loose group of 20 to 30 friends frequented Da Brando on a regular basis, although they didn't go there every evening and sometimes only a handful dropped in. They were professionals - engineers, doctors, lawyers, teachers - who liked a good time, and would congregate for hours in the back rooms, playing cards, talking into the small hours. Not many had children. They seemed to have quite a lot of disposable income at their command, which resulted in a free-flowing hospitality. At the heart of the group were Carla and Fulvio, a couple who showed huge generosity not just in terms of money but time, practical help and above all learning Italian. For months after I arrived in Udine we would end up in Neveo's till late, with our heads bursting with the effort of conversation. I don't remember anybody making fun of me despite my lengthy and embarrassing attempts at the language, and I can't think of any English person who would have been so liberal with their help over such a long period. Fulvio was olive-dark, youthfully smooth-complexioned, with a slight limp from childhood polio. Sadly, I heard from Carla that he died in August 2018 after a long and painful illness. He was central to my education and induction into Friuli and Italy. Full of zest for the good things. A quick mind highly attuned to the absurdities of life, a full-throated laugh when commenting on them. Unbelievably kind and generous. I don't think I ever managed to pay after spending an evening out with him. Fulvio, giving to a fault, had always mysteriously settled the bill.  He once described a terribly hung-over morning when he was driving to Trieste for a meeting. Every time he looked in the rear-view mirror, there was a monkey dancing on the rear parcel shelf. "La scimmia, la scimmia!" After I'd been back in England for two years, I returned with my friend Guy over the New Year period. Travelling via Milan, we drove a hire car up into the mountains to the north-east and joined Fulvio, Carla and others for a few days' skiing. Fulvio commented that I was skiing madly, with the "scimmia addosso" - with the monkey on my back.

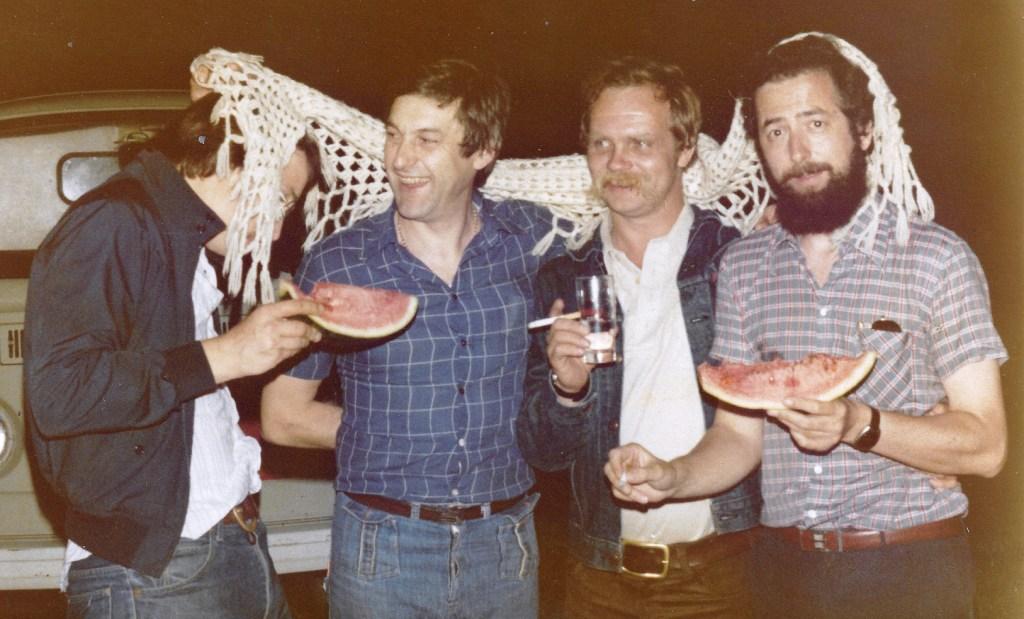

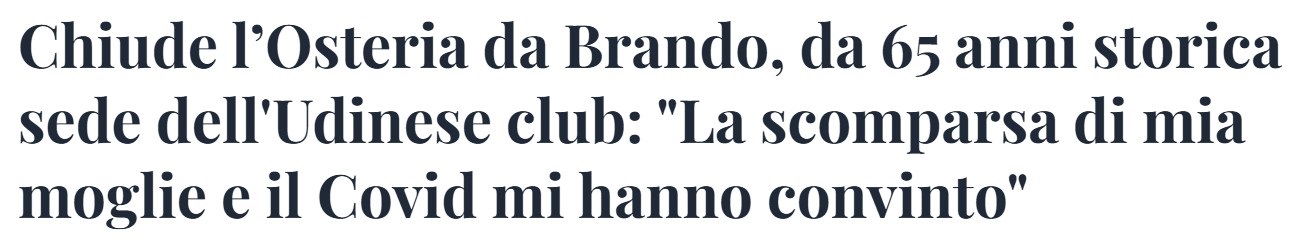

Guy and I became short of money, and we decided to ask Fulvio if he could lend us 50,000 lire - cash wasn't so easy to get hold of then, prior to the ubiquitous hole-in-the-wall. I asked Fulvio, and he handed over the money without a second's thought. I then did the most bizarre thing, and said to Fulvio, "E diecimila per la scimmia!" ("And another 10,000 for the monkey!"). Not even a blink - I had the extra cash. He was devoted to Carla, and she to him. Very different but intertwined personalities. Carla was charming, fit, bouncy, full of enquiry. She could give the impression that my halting attempts at serious discussion in Italian were jewels of meaning. Easy to be with, easy to talk to, with a brightness and welcome in her eye. For a while, a group of us had semi-formal Italian lessons with her. She was a teacher, Italian, Latin and Ancient Greek; so knew how to do it. I chose telling jokes as my assignments, and developed a small repertoire that proved invaluable later when called upon by Italian friends, although some were rather blue. They opened up a lot of the nearby world to us. We went skiing with Fulvio's brother, Roberto, and his friend Ernesto. Ernesto was a superb skier, almost paraded by Roberto, who always had something to hype up (sadly, he was to die young after I left Italy). One summer, we went down the Yugoslav coast to a nudist camp with most of the core group, days spent swimming, fishing, eating and drinking. I still find the idea of playing volleyball stark naked quite odd. So many wobbly bits. Isa, Carla's sister, was there with her husband Piero, whose brother Alberto also came with his wife. Both men are dead now, not entirely missed. There was an unattractive oafishness about them. I treasure one little encounter Chris had with Piero. Early one evening Chris wandered into the Bar Savio in Piazza XX Settembre, at that time a newly opened, modern, aluminium-and-beechwood venue favoured by the Brando crowd for "aperativi" after work. Piero was leaning on the bar, morose as ever. He met Chris' greeting with a grunt. Undaunted, Chris persisted. "All'ora, Piero, come stai?" ("So, Piero, how are you?"). A brief silence, then Piero barked, "Stanco, stufo e incazzato!" ("Tired, fed up and angry!"). I understand the exchange didn't continue for long. Back to Neveo's front bar, where Rosso was often to be found. He was a small, wizened man with a bulbous and gnarled nose. Surprisingly, his nickname came from his reddish, thinning hair, not from the colour of his nose nor the wine he drank. He spoke in a hoarse roar, often accompanied by dramatic gestures and lofty pronouncements addressed to whomever might listen. He lived by doing rare odd jobs, relying heavily on his ancient "motorino", a tiny grey 3-wheeled motorcycle pick-up truck. There was consternation one evening when someone ran in declaring that a man was arriving with a lion. It was true, although it turned out to be a lion cub, albeit a large one, at the end of a leash. The front bar regulars backed away, some leaping to sit on the bar, all except Rosso, who remained seated at his table by the door, spreading his arms wide in welcome. After making a few come-hither mewing noises to the cub, he turned to Neveo and demanded two steaks and a bottle of champagne. "E pago io!" ("And I'm paying!"). I'm not sure whether this last cry was an expression of his largesse or reassurance to Neveo that he was in the money that day. I wondered quite who the order was for, and shortly, all became clear. Quite brilliantly, fifteen minutes later Neveo arrived with a trolley carrying two steaks and a laden ice bucket. Rosso laid one plate on the floor for a very pleased cub, tucked into the other himself and offered champagne to all around him. I taught a group of nurses at Udine hospital on a Friday morning. I stopped by Neveo's to get an expresso before getting on the bus. Rosso was standing at the front bar drinking a glass of red wine. There was a hum of desultory conversation, a few others taking their time over coffee and the newspapers. After about ten minutes, in the quiet of this low-key atmosphere, Rosso banged his empty glass down and swung round to address the room. "OK, everybody, I'm off to work now. Salutations to you all. May you have a profitable day!", and a parting "Buona giornata, Professore" to me. He made his way heavily towards the front entrance. When he got there, with the door half open, hand on handle, he paused. Seconds passed, then he released the door, came a few steps back into the room and said gently, "Hold on a minute. I haven't got a job." I once passed up a genuine Saturday night dinner invitation when Rosso prevailed upon me to meet him and his brother at Neveo's instead. He insisted that his brother had an astonishing skill, that he could command small songbirds to do his bidding - to fly across the room to order, perch on his finger, flap their wings, sing. What is more, Rosso asserted, "Parla l'inglese meglio di voi" - "He speaks English better than you." He emphasised that this was a once-in-a-lifetime un-missable opportunity and I accepted. I arrived at the appointed time and ordered a glass of wine. Half-an-hour passed, a full hour. No sign of Rosso. Of course, he never showed. I judge this the nadir of my entire social life, stood up by a small drunk with a big nose and a rusty 3-wheeler on an evening when I might have been treated to an exquisite meal in erudite company in the summery foothills of the Dolomites. The same 3-wheeler was the star - or maybe not - of another typically Rosso event. Several of us were in the front bar mid-evening and needed to eat. We decided to cross the square to the pizzeria da Pierino directly opposite. A journey on foot of some 100 metres as the crow flies. Rosso heard our plans and presented himself at our table. "Ladies and gentlemen," he boomed with a wide sweep of his arm, "Let me put myself at your service. My humble vehicle awaits outside and I will transport you." OK, Rosso, we agreed, and trooped out of the front door. There was the motorino parked eccentrically on the pavement. "All aboard, my friends!" Six people got into the flat-bed rear section. Rosso clambered into the cab and kick-started the engine into life. We set off. Motor howling, a blue plume of clutch-smoke, horrible crashing of gears, at close to three miles an hour we screamed round the inner curve of Piazzale Cella, coming to rest mid-carriageway opposite da Pierino some twenty-five seconds later. We climbed off and thanked Rosso. It had been a close-run thing, the motorino had struggled. Rosso was apoplectic. As we walked into the pizzeria and looked back, he was kicking the motorino, berating its performance. Then he bent down and hauled upwards on the bodywork, tipping the truck onto its side in the middle of the 2-lane ring-road roundabout. We left him there dodging and abusing traffic, shaking his fists in rage. Da Brando was a family business. Brando was Neveo's late father. His portrait hung above the door to the card room, a stern face with dark hair and moustache, rather like a well-fed Hitler. While Neveo set the manic tone of the place, the engine room was staffed by his wife, Teresa, and sister, Anna. Both were short and plump, Teresa blonde and very pretty, Anna dark. Neither smiled much, although both could break into loud laughter unexpectedly, usually because of the absurd behaviour of their customers. They padded silently through the rooms, maintaining order; indeed, they administered discipline, accepted unquestioningly by the rough-edged clientele. When I went into the bar on three occasions to find Neveo during my nostalgic 2002 visit, Anna was always there. Neveo had gone to the mountains for mushrooms one day, to the sea for fish another, and nobody knew where he was the other time. 2018 The original da Brando has been closed for many years. I heard that extreme dilapidation made its upkeep untenable. Neveo moved to a much smaller new bar across Piazzale Cella at the foot of one of the modern blocks. Nothing like the old place with its many rooms, each with its particular characteristic, but at least it's there and so is Neveo. It's still the popular venue for Udinese "tifosi"; note the banner and flags outside. I'm pleased to see that "Trippe" are top of the list on the pavement menu blackboard (see "Food" section for an explanation). The picture of his father is on the wall behind the bar.    February 2026  We're three months away from the 50th anniversary of the earthquake of 1976, so I've been toying with the idea of a return visit to mark the night of 6 maggio. Scouring the web for information about any commemorative events, I stumbled on the above 5-year-old headline from local rag Messagero Veneto. Neveo gave up the bar in 2021, deciding that he'd had enough after the 2020 death from Covid of his wife Teresa; his sister Anna was also gravely ill.  The articles I found told me much that I didn't know. His surname is Marazzato. I say "is" because although I heard from Carla on my 2023 visit that he might be dead, I don't know for sure; I learnt from this recent research that he was born in 1942, so 84 now. The newspaper also spelled his name Nevio, rather than the Neveo I've always used. The Brando moniker came from his father, the rather magnificently named Ildebrando Sante Marazzato, who had moved to Udine from the comune of Trebaseleghe in the province of Padova - the family were Venetian originally - and after managing the Al Ragno hotel on Viale Volontari della Libertą had in 1956 taken over the then-named Ai Provinciali with his wife Erminia. Neveo's wife - they were married 54 years - Teresa was also an out-of-towner, but only from as far as Marano Lagunare, a little waterfront town on the Marano lagoon, 20-odd miles south of Udine. A tough cookie - "veramente tosta", said the president of the Udinese fan club - she had her own obit headline in the Messagero Veneto in December 2020.  A lion's share of the archive column inches, as the headlines attest, centres on the Udinese football fan connection. The Da Brando section of Udinese Club was founded in 1973, only two years before I arrived, and the bar really was a true home. Neveo was vice-president on the first board, and also treasurer. He's fourth from the right in the front row below.  A slightly dodgy-looking bunch, I always thought when I wandered into the large dining room at the rear of Da Brando. Like a Masonic lodge in session. |